Maps: The Big Picture

Originally published in the Santa Cruz Sentinel, March 7, 2015

Maps help fulfill “the need to visualize our little

lives in the context of a grander scale.”

-Ken Jennings

Before I take a trip to an unfamiliar place, I go to

AAA to get a free map of the area. Yes, I have a cell phone, but a fold-out map

gives me the big picture and all the details at the same time. My cell phone, with its tiny screen, can’t do

that. After I’ve unpacked my bags, it’s

time to unfold the map, spread it out on the bed, and plan my next move. Once I

know my destination, the cell phone will help me find my way.

Maps: Depth and comprehensiveness

The big picture is important, and so, maps still serve

a useful purpose—they show you things you don’t know, in relation to things you

do know. If you decide you need to know where Ukraine is for example, a map

will show you that it’s two countries away from Germany, with Poland in

between. It will also show you that it shares the Black Sea coastline with

Russia and Turkey and three other countries. And yes, I had to look at a map to

tell you that.

Maps help us understand what’s going on in the world. “We

live in an increasingly inter-linked world where developments an ocean away

affect our daily lives in countless ways,” says Ken Jennings of “Jeopardy!”

fame. If we know where Ukraine, or North Korea, or Nigeria is on the world map,

we can “synthesize and remember the events that we hear about taking place

there.” Otherwise, they just become

names that wash over us.

Jennings wrote the book “Maphead” in 2011 about his

life-long fascination with maps. “My childhood love of maps…was something much

more than casual weirdness,” he writes. “I could literally look at maps for

hours. Each page of an atlas was an almost inexhaustible trove of names and

shapes and places, and I relished that sense of depth, of comprehensiveness.”

In “Maphead” Jennings sees geographic illiteracy as a serious societal

problem in the U.S., and gives lots of examples including a National Geographic

poll showing that one in ten American college students can’t find California or

Texas on a map. Geographers trace our decline in geographic knowledge to the

widespread adoption of “social studies” in grade schools over clear-cut history

and geography classes in the 1960s and 1970s. “The United States is now the

only country in the developed world where a student can go from preschool to

grad school without ever cracking a geography text,” says Jennings.

Geography of course, isn’t just about reading maps or

understanding the Earth’s physical features. It’s about how humans relate to

the planet. “Geography explains the

map: why this city is on this river, why this canyon is deeper than that one,

why the language spoken here is related to the one spoken there—even perhaps,

why this nation is rich and that one is poor,” says Jennings.

A great example of maps that help us make sense of our

complex relationship to the planet is “Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas” by

Rebecca Solnit. Her book features maps (created by various artists), that make

surprising and intriguing connections. “Poison/Palate” shows the proximity of gourmet

treasures to toxic waste in the Bay Area. “Dharma Wheels and Fish Ladders”

plots the little-noticed salmon migrations in the Bay Area, beside the practice

of Zen Buddhism. And “The Names before the Names” charts the 140 or so

indigenous tribes that lived in the Bay Area prior to 1769—an astounding

density of communities which have since completely vanished.

Mapmaking: A

reflection of the maker

All mapmakers choose what to include as well as what

to leave out—and accordingly, a map is a reflection of its maker and how it

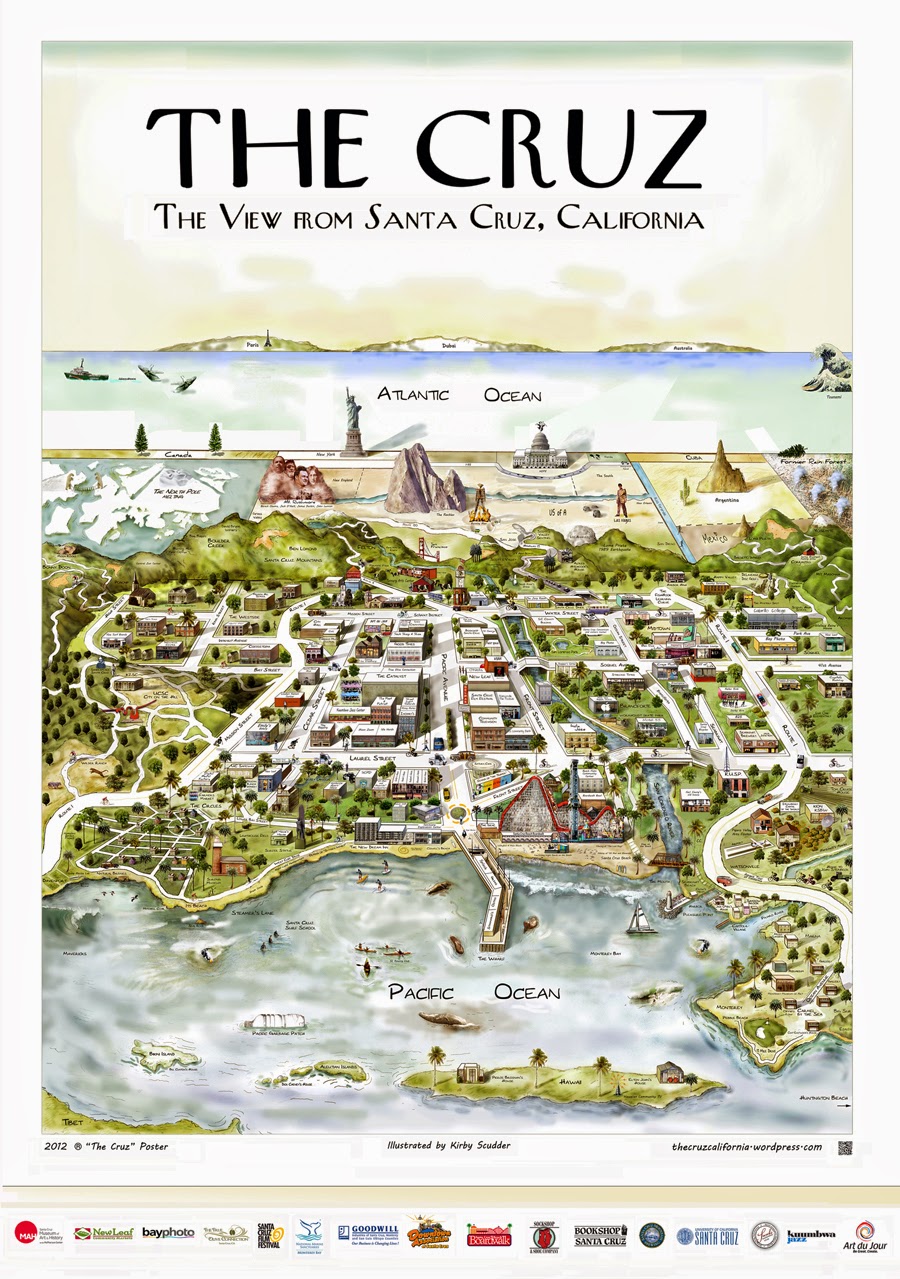

will be used. Santa Cruz artist Kirby Scudder created a poster of Santa Cruz in

2012 that included only the features he found most emblematic of the city. To

create large city maps, he uses Google Earth for research and Photoshop with a

Wacom tablet to painstakingly draw people, vehicles, buildings, shadows, land

and water features from an angled aerial perspective. He takes great liberties

with spatial accuracy—bending and foreshortening land masses, selectively showing

only the resonant landmarks, streets and buildings he believes are the essence

of “The Cruz.”

Historically, mapmakers have always had a point of

view, and many wanted to tell stories of adventure and discovery. They rarely

had the firsthand experience they needed to be certain of all the details on

their maps, so they listened to surveyors and explorers, read books and studied

existing maps, and made educated guesses. Oftentimes, they made mistakes. One

of my favorite books of historical maps is Vincent Virga’s “California, Mapping

the Golden State through History” which begins with the famous 1650 Map of

California shown as an island. By the mid 1700s, California was finally attached

to the rest of the continent on maps, but with very few details, remaining on

the fringes of the world as the Europeans knew it.

Mapmakers are also influenced by commercial concerns:

they want to sell maps. A U.S. map produced in 1849 shows most of North

American in great detail with two insets on either side: one of South America,

and the other of the California gold country, to make it more appealing to map-buying

gold-seekers.

Mapmakers are also influenced by commercial concerns:

they want to sell maps. A U.S. map produced in 1849 shows most of North

American in great detail with two insets on either side: one of South America,

and the other of the California gold country, to make it more appealing to map-buying

gold-seekers.

Some of the best old maps of California are

romanticized versions of the frontier. They depict the carefully planned streets

and grandest structures of farm cities like Fresno and Bakersfield at the turn

of the 20th century from that same vanishing point perspective in

the sky as in Kirby Scudder’s Santa Cruz. But each map is bordered with a

series of hand-tinted photos or drawings of various businesses, impressive homes

and civic structures. These flat, hot central valley towns were trying to

attract new residents by making their city look substantial, thriving and full

of opportunity.

|

“Map of Bakersfield, California, 1901”

from the Library of Congress

website, LOC.gov

|

On the Map

However accurate a map is intended to be, it can only

offer a snapshot of what things were like at a certain point in time, and is

already out-of-date when published. Fortunately, most maps are not intended to

accurately describe spatial relationships. They are intended to make a point.

Whether you use GPS, Google Earth or paper, maps are essentially a collection

of cartographic symbols—straight and wavy lines that help us make sense of the

world and our place in it.

.jpg)